This website uses a variety of cookies, which you consent to if you continue to use this site. You can read our Privacy Policy for

details about how these cookies are used, and to grant or withdraw your consent for certain types of cookies.

Selecting a Primary Device: Choosing a Weir or Flume Style

In the first article of this series on Selecting a Primary Device we discussed criteria that can be used to select between a weir and a flume. Now our attention turns to selecting a particular style of weir or flume.

The choice of device style is normally dictated by the three considerations:

- Site configuration

- Flow stream composition

- Range of expected flows

Site Configuration

Some site considerations are shared between weirs and flume (e.g. do the upstream channel banks limit the amount of head that the device can generate), while others are specific to the type of device [e.g. is there room for sufficient aeration (for a weir)].

Selecting a style of device that is similar to that of the channel is one way of managing installation costs – so long as the flume adequately covers the range of anticipated flows.

Weirs

For a weir to properly operate the nappe (the sheet of water passing over the weir plate crest) must be adequately aerated. Poor aeration of the nappe may result in it clinging to the downstream face of the weir. Insufficient aeration, whether by poor sidewall geometry or insufficient vertical drop from the weir crest to the downstream water surface can increase discharge by as much as 25%.

Consideration, therefore, must be given as to whether or not the site either naturally or artificially can provide adequate aeration.

Weir pool sizing is another consideration when selecting among different weir styles. All weirs require adequate upstream weir pools to properly condition the flow as it approaches the weir crest, but some styles (e.g. V-notch) generally require wider / longer / higher weir pools than other styles for the same flow rate.

Flumes

Flumes are available in a wide variety of cross-sections:

- Rectangular (Parshall, H flume, Montana, and Cutthroat)

- Trapezoidal (RBC and Trapezoidal)

- U-shaped (Palmer Bowlus and Leopold-Lagco)

Many times the shape of the channel is the deciding factor on which style of flume to use for a particular application.

For example, when installing a flume in a box culvert, the natural consideration would be a flume with a rectangular cross-section (Parshall, H-flume, Montana, and Cutthroat) – excluding those with trapezoidal or U-shapes. Similarly RBC or Trapezoidal flumes would be the flumes of choice for an irrigation furrow as they conform to the shape of the channel. Selecting a flume that is similar in cross-section as the channel can decrease installation costs and increase measurement accuracy.

For sites with relatively flat gradients – where either the channel cannot be modified, the channel sidewalls are low, or where discharge cannot free-spill off the end of the flume – Cutthroat, Trapezoidal, and RBC flumes work well.

Where free-spilling discharge out of the flume is possible, H-flumes, Montana, and Parshall flumes are good choices.

For piped flows, remember that many flumes are available with end adapters or bulkheads, which can be provided with pipe stubs, caulking collars, or flanges. Even H-flumes are available with inlet bulkheads attached to the approach section and custom discharge structures to connect the flume to piping.

However, some flumes can be readily adapted to different channel cross-sections relatively easily (e.g. Trapezoidal fumes in pips or U-channels). So matching the flume’s cross-section to the channel is not always a deciding factor.

Flow Stream Composition

For weirs, flow stream composition is generally not as great a selection criterion as it is with flumes. That is not to say, though, that it is entirely unimportant. The primary decision here is whether there is debris in the flow stream that would accumulate in a V-notch weir’s restriction. If debris is present, then a Cipolletti or Rectangular weir (with or without end contractions) would be a better selection unless regular maintenance can be performed to keep the V-notch clear.

Flumes in general are quite good at passing solids; however some flumes are better than others in this respect. Flumes with elevated throats (RBC, Palmer Bowlus, and Leopold-Lagco) tend to accumulate more upstream silt, sediment, and debris than those with flat floors (Parshall, H-flume, Trapezoidal, and Montana).

Additionally, flumes with narrow throats (those under 3-inches [7.62 cm] in width) should not be used on unscreened wastewater (those with sanitary solids) due to the likelihood of clogging.

Range of Expected Flows

The ability of a primary device (weir or flume) to handle the range of expected flows is of particular importance - usually more so than the configuraiton of the site or the flow stream composition. If the device chosen cannot adequately measure the range of expected flows, then there is usually little reason to proceed with an installation.

Weirs

For an application where high flow rates are expected, a Cipolletti or Rectangular weir (with or without end contractions) would be a natural choice over a V-notch weir. While the V-notch may be able to handle the flows, the size and cost of the installation would be greater.

The choice of a weir style can be somewhat complicated if flow is banded in both a low flow and a high flow regime. Where flow banding is present or where the flows are expected to otherwise widely vary, a compound weir may be considered. Here a 90 degree V-notch (or similar) is designed to handle the lower flows and cut into a larger (usually Cipolletti or Rectangular) weir (which is designed to handle the higher flows).

From low to high flows, the natural progress of weir styles is:

- V-notch

- Cipolletti

- Rectangular with end contractions

- Rectangular without end contractions

Flumes

Where low flows are expected, Trapezoidal, HS-flumes, and (to a lesser extent) RBC flumes are commonly used – although smaller sizes of Parshall, Montana, and Cutthroat may be suitable depending upon the flow stream composition.

Large flows tend to be the domain of Parshall and HL flumes. Montana flumes (short Parshalls) are theoretically possible, although their unique discharge requirements mean that they are rarely applied in sizes larger than 36-inches.

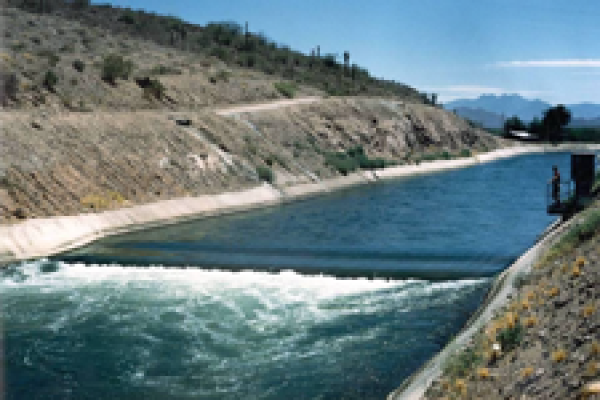

For very large flows, Parshall flumes (usually concrete) are used exclusively.

Some styles of flumes have many different standard sizes available (Parshall / Montana – 22, Cutthroat 16, HS / H / HL – 14), while others are limited in their offerings (RBC – 5, Trapezoidal – 9). Naturally the fewer the number of sizes, the less likelihood there is that a flume of a particular style will fit the range of flows.

For applications where flows are expected to increase dramatically over time, some flumes may be provided in nested configurations where a smaller flume is nested in a larger flume. Here the inner flume is sized to handle the initial flows, while the outer flume is designed to handle future flows. As the flows increase overtime, the inner flume is removed (and usually discarded) leaving the outer flume to measure the flow. For applications where flows are expected to seasonally fluctuate (resorts, fruit / vegetable canning operations, etc.) the inner flume may be removed, but later replaced as flows peak over several months and then resume a lower normal flow rate.

Usually when flumes are nested, the same style of flumes are used (e.g. Parshall in a Parshall), this is not, however, always the case. Sometimes a different style of flume will better handle the initial flows than will handle the future flows. Here dissimilar flumes (e.g. Trapezoidal in a Cutthroat) may be used.

Previously…

In our last article we covered: Choosing a Weir or a Flume

Up Next…

In the next article we cover: Choosing a Weir or Flume Size

Image: Oulu University Library

Related Blog Posts

Explore more insights in our blog.

LOCATIONS IN ATLANTA, GA & BOISE, ID